Teaching with Complex Text - It's a Complex Thing To Do

- Brent Conway

- Jan 30, 2022

- 6 min read

We often hear the phrase “Complex Text” but several questions come to mind regarding Complex Text. What does that actually mean, and what makes a text complex? Why do we need to teach with complex text, and most importantly, how do we do it?

An obvious component of a complex text is the vocabulary that is included. We wrote in this blog in November about how vocabulary plays a critical role in building background knowledge and giving students access to various types of text. However, there are numerous other considerations for text complexity which are often the stumbling blocks for students to understand what a text is trying to convey, and what meaning a student should take away from reading the text. Student Achievement Partners in 2014 organized complexity into 4 dimensions that all impact how a text can be complex:

Meaning/Purpose

Knowledge Demands

Text structure

Language

Text complexity is identified in the Common Core standards and in the MA Frameworks from 2017 as a critical aspect to students' success with fiction and non-fiction texts. MA DESE adopted new Reading, Writing and Language Standards - but aspects of this apply to ALL content areas. These changes came from numerous studies that showed the demands that college and careers place on readers are either the same or have increased over the last fifty years, but our instructional approach has been to lower the complexity of K-12 reading texts for students. The Common Core State Standards Initiative identified 3 Big Shifts we MUST all adapt to.

Regular practice with complex texts and their academic language

Reading, writing, and speaking grounded in evidence from texts, both literary and informational

Building knowledge through content-rich nonfiction

To further understand the impact all of this has on how a reader comprehends a text, we need look no further than Scarborough’s Rope. Focusing primarily on the “upper” strands where language comprehension is organized, we see many connections to definitions on text complexity. Knowledge demands or background knowledge can be mitigated by teaching texts as part of ongoing efforts to build knowledge, rather than teaching unconnected texts for skill practice. Although the random texts may be complex, the information has no connection to prior work, content, reading, or discussion. Text sets, integrated student discourse, and writing help build knowledge and prevent the need to front load all of the context and even Tier 3 vocabulary for students. When content areas are departmentalized like in a middle school or high school, it becomes even more critical for the all content area teachers to see themselves as teachers of literacy. After all, most content text books contain very complex text, that require academic vocabulary, an ability to make use of text features but also to navigate language structures that may be unique and challenging.

So, assuming we are introducing a complex text as part of ongoing similar content, and we are teaching vocabulary to students from the text that is needed for understanding, is useful and important, or has potential for growth with word learning, we are mitigating the impact those components of Scarborough’s rope has on accessing a complex text. The rest is really about understanding text structure based on the type or genre and understanding the language at the sentence level and the paragraph level. This includes breaking down sentences for syntax, coherence with clauses, and pronouns, etc.

In the past, many educational programs and teachers have simply altered the text or provided a text that was not as complex, so the student could read the text independently and avoid frustration. This is especially true for students still struggling to decode and therefore cannot access the language of the text independently. However, that is not scaffolding; that is lowering the expectations, and all students need access to grade level content and language regardless of their ability to fluently decode. Students can only learn how to read complex text…by reading complex text. It is how teachers break down the text and scaffold it that makes this possible for many students.

Dr. Tim Shanahan, an international literacy expert, presents and writes on this topic frequently. In his shared presentations on language and text structure, he outlines the considerations teachers should make when planning from a complex text in order to support the student learning how to comprehend it, and then transfer that skill to future reading of complex texts.

Scaffolding Text Features

Complexity of ideas/content (Purpose & Knowledge)

Match of text and reader prior knowledge (Knowledge)

Complexity of vocabulary (Knowledge & Language)

Complexity of syntax (Language)

Complexity of coherence (Language)

Familiarity of genre demands (Structure & Language)

Complexity of text organization (Structure & Language)

Subtlety of author’s tone (Purpose)

Sophistication of literary devices or data-presentation devices (Purpose & Language)

Recently in one of our 3rd Grade classes, a teacher encountered an excerpt from a non-fiction text the class had been reading, where the students were asked to identify the most important event from the 5 paragraphs. The text was Galileo’s Starry Night by Kelly Terwilliger and it has a Lexile level of 860, placing it in the mid to upper range for 4th grade, making it a complex text for 3rd graders. Despite knowing most of the vocabulary, having two “Tier 2” words (gusto and marveled) pre taught and having read other texts about the similar content, the students found the text challenging to comprehend and to answer the question. The teacher recognized that the coherence and the syntax was the challenge and quickly scaffolded the lesson.

The teacher connected the subjects to the verbs, using highlighted arrows. She broke apart the sentences and clauses and added key question words such as Who and When and drew a box around the action/verbs. This helped the students to focus on the information that was important. The students were then able to answer the prompt. This is work at the sentence level which is where most will find the need exists but it can go to the paragraph level too.

One student wrote “The most important event was in 1609. Galileo was listening to a friend who described an invention called a spyglass.”

If we plan from the text, and anticipate where our students may struggle, we can provide a scaffold for all students that they can begin to transfer into their own reading. For those students who require more intensive scaffolds, we can continue to do that individually or in small groups ongoing progress.

Understanding general grammar and parts of speech, on its own, does little to help one be a better reader or writer. But knowing what each part of speech does for sentence level meaning can help a student think critically about the text they have read. In the past we have been taught the definition of parts of speech, like a noun is a person, place, or thing. Yet, the more effective understanding is to attach parts of speech to how they help us understand text. Once one can construct meaning that way, they can also deconstruct a sentence to create meaning.

Question - Semantic Meaning or “clue” | Part of Speech |

Who, what, or whose? | Pronoun |

Who or what? | Noun |

Is or was doing? | Verb |

Which one, how many, what kind? | Adjective |

When, where, how, why? | Adverb |

What is the relationship between the words before and after? | Preposition |

What is connected or needs to be glued together? | Conjunction |

The same can be done for text in High School. The complexity of “Letter from Birmingham Jail” by Martin Luther King, Jr. (1964) has many layers. Again, assuming it is not being used as a random passage to practice reading complex text, and that it was used as a primary source from a 10th grade US History II class or a Civics class, students would have enough of the context and knowledge to understand the background of the text. The potential challenges for students may include: vocabulary, background information, complex text structure, and/or tone of text.

Reading such a text in class would require multiple reads. The teacher reading aloud, the students reading and then annotating, followed by another read where they are seeking answers to text dependent questions.

For the students to read the entire text and comprehend it, the teacher may want to first discuss the nature of “interconnectedness” in the text and make one annotated connection with a critical point. The statement of “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere” should be connected back to the prior paragraph where Dr. King states “...I am here in Birmingham because injustice is here.” If students have this type of scaffold, it will help them to understand the tone and understand the structure with repetitive use of clauses for points of connections.

Reading complex text can be hard for students, but it can be even harder for teachers to teach. There are many things to consider for how students may struggle with a text. The vocabulary is a good starting point but thinking about syntax, clauses and structure and how to scaffold it for students will help students make sense of text that we had not thought they were capable of understanding.

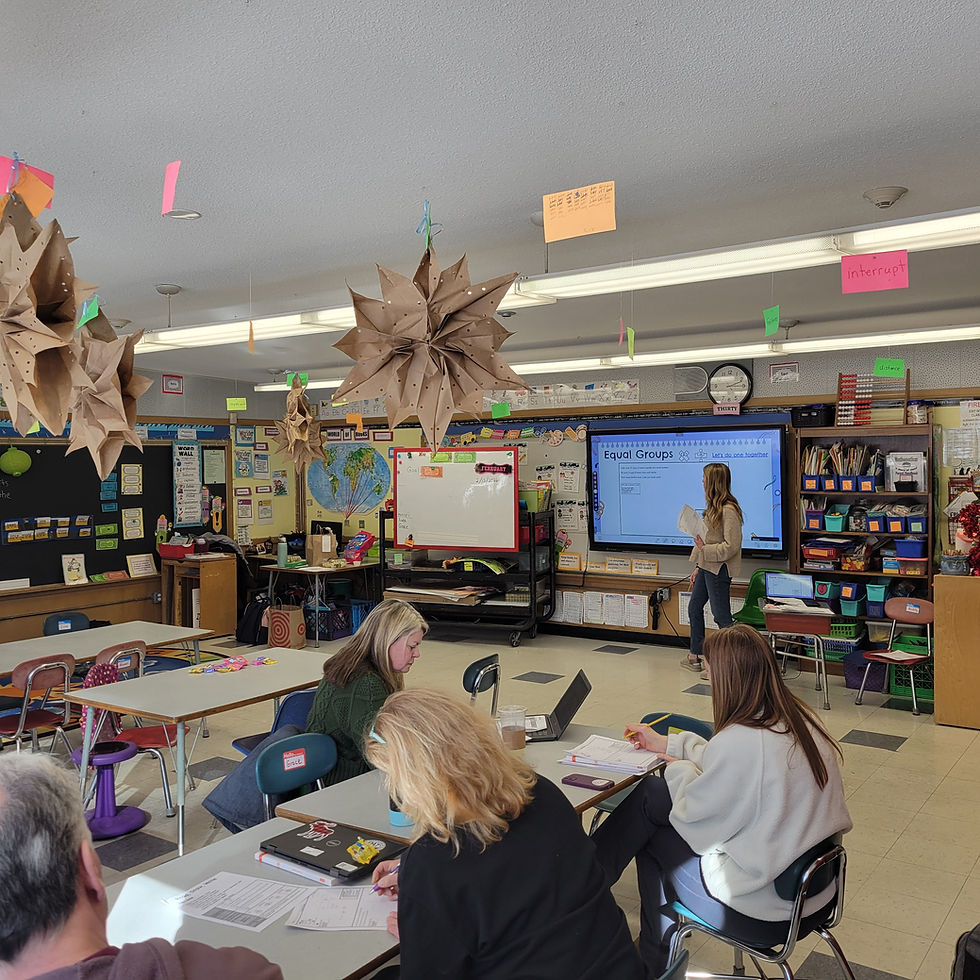

Pentucket teachers are learning more about how to teach with complex text. Recently added text resources at the Middle School and High School along with high quality literacy and math curriculum with Eureka and Wit and Wisdom at Elementary School have helped teachers to see the difference but also the need for direct instruction and scaffolds for students. Professional development will be ongoing during this school year and into next with support from instructional coaches. Maintaining high expectations for students is crucial, but so is knowing how to support all students to meet those expectations.

Brent Conway, Assistant Superintendent

Jen Hogan, K-6 Literacy & Humanities Coordinator & Coach

Dr. Robin Doherty, Gr. 7-12 Curriculum and Instruction Coordinator

Comments