Screen and Intervene - Early Identification for Literacy Skills

- Brent Conway

- Jun 29, 2023

- 9 min read

As the “science of reading” seems to be taking hold in districts across the country, it is a phrase that has roots that are not so new. We have known for a long time that teaching students to read requires an early focus on phonics so that students develop the necessary skills to decode and encode (spell) to tackle words they encounter in text and to write. The “science of reading” though is not limited to phonics, as some may have you believe. The staff in Pentucket know this and they have invested countless hours with professional development. We have focused our professional learning on learning new curriculum to implement so that students are both learning to decode fluently and learning rich vocabulary, language structures and building knowledge that helps them to make connections with text and comprehend complex text.

It is true however, that a focus on those early foundational skills associated with strong decoding and fluent word reading are key to a student’s success and allows them to put more thought and mental energy into understanding the texts they encounter as they get older. Teachers in all grades and subjects are “teachers of reading” as the process of learning to be a skilled reader is always in development.

Beyond the professional development and curriculum implementation, our staff have always become quite adept at using and leveraging critical data points to assess and monitor student progress. Even during the pandemic and school interruptions, our elementary schools continued to pay close attention to data points that are scientifically proven to be predictors of reading success. For those students who are not meeting the indemnified benchmarks, we know what skill they are precisely struggling with and we can provide immediate targeted instruction and continue to intensify as needed and as the data indicates. Using valid and reliable screening tools is one of the most important things our schools can do to ensure that students are progressing with foundational skills.

Our state standards and the national common core standards all identify foundational skills expectations of students from Kindergarten to Grade 2 or 3. However after grade 3, there is little mention of foundational skill expectations for students, except that students continue to read fluently. The focus of reading standards at that point shift to more language development, vocabulary and comprehension based outcomes. This is developmentally appropriate and supported by decades of research. In fact, and not without controversy, many states have enacted recent legislation that are titled “Read by Grade 3” laws. While these vary from state to state and some even have retention components for students who are not meeting the expectations by grade three, they are all rooted in an evidence based approach to ensuring students have foundational skills intact by the time they leave 3rd grade.

Why the focus on 3rd Grade?

There is little argument that for students who struggle to read proficiently, other aspects of school can become more challenging and there can be lifelong implications as well. The 2010 Annie E. Casey Foundation Report - Early Warning! - Why Reading by the End of Third Grade Matters - lays out numerous statistics to explain the importance and what is at stake for individuals, our communities and even the economy. We also know that the only common standardized method of assessment of reading comes from state tests, like the MCAS in MA and the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) - which also starts in grade 3. The problem is, this is the first point of common warning for so many families and schools that a student may be struggling to learn to read… and it’s too late.

For students who are not proficient readers by the end of 3rd grade, they are at tremendous risk for always being a struggling reader and the path to “catch up” is a long and challenging one. Students who are in need of intensive reading support after 3rd grade can catch up, but it becomes harder on them as students, missing other classes and often at the expense of other interests. Research has shown this for decades, which is why Pentucket has put such efforts into the early identification of lagging reading skills and implemented a systematic approach to providing students with evidence based, targeted and intensive interventions through a Tiered Literacy Model.

Since 2019, we have also been working with the MA Department of Elementary and Secondary Education on projects such as the Dyslexia Guidelines, the Mass Literacy Initiative, The High Quality Instructional Materials program, and the newly released in June of 2023 - Early Literacy Screening Guidance.

The infographic below highlights the brain science behind the work we do and why the Department of Education is also focused on this work and the original can be found on the EAB Website.

Our own data supports this work

As a district, we have been using the DIBELS 8 literacy screening tool since 2018. In the 2018-2019 school year only 68% of students in grades K-3 in Pentucket were meeting the end of the year expectations in the early literacy skills. This meant that nearly ⅓ of our students in K-3 demonstrated some risk or high risk factors for reading failure. Simply having this information is not enough- we need to use the data to make improvements. Our teachers worked to implement a system, and took on the charge of ensuring all students made annual growth; and for those who were behind, we helped them to make “catch up growth”. Lowering their risk for future reading difficulties became a mission. Even amidst the pandemic and challenges that brought about, at the end of the 22-23 school year, we now have 81% of students in K-3 meeting grade level expectations with a very small amount in the “high risk” category. The growth is worth celebrating.

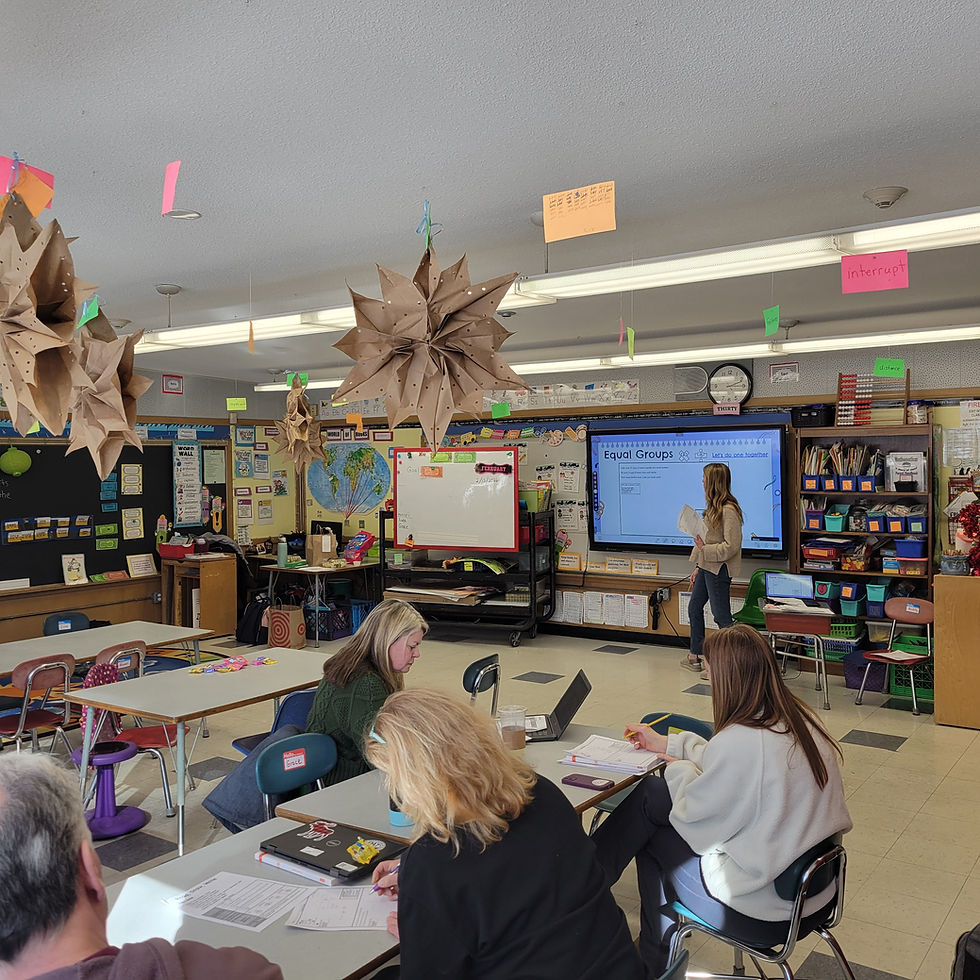

We have worked to help staff understand the critical need to address these skills early. Often the teachers working on these skills for students never get to see the benefits as the student makes continuous progress and emerges as a skilled reader a year or two later. That has not stopped the staff though as they see each student as their responsibility and take on the shared ownership of their success. We have worked to move away from beliefs and thinking about learning to read not rooted in the science. Even if they were well intended, these were sometimes reflected in comments or approaches. The phrase “let’s wait and see” has been replaced with, “let’s target that skill and monitor the progress.” It is a paradigm shift.

These changes in thinking also work to combat common misconceptions. As the infographic above shows, the brains of kids all learn to read generally the same way. It’s just for some it can seem rather effortless when for others, they need more practice, more instruction and more intensity with the focus and target of the work. It is not true that “Kids learn to read differently.” We all actually learn the same way but the intensity of instruction that is needed may vary.

We don’t just use a data point and “prescribe” an intervention either. While we are using a systems approach and data, we know each student is an individual. We meet as teams multiple times per year and consider data and other aspects - then design targeted and direct instruction that focuses on the literacy skill needs for students, using evidence based approaches. Some students need more time, more intense instruction, more focused feedback or more repetition through practice to make skills automatic. We also coordinate our efforts to make sure that instruction from one professional is not undermining the instruction from another. A clear and coherent curriculum is key to this, as are regular meetings where we review student progress and discuss what we are doing to help a student make gains. While other students seem to grasp the taught concepts rather quickly and effortlessly, we know this approach is critical for others. This is at the heart of a Tiered System for literacy instruction.

Key reading scores “risk factors”

Using a screener like the DIBELS focuses on those key skills. We often use the four color system that correlates to the risk factor score from DIBELS. Blues and Greens generally mean that the score on that test suggests that the students have minimal risk for future reading struggles, whereas a yellow score indicates there is “some risk” and a red score suggests “at-risk” for developing reading proficiency. The DIBELS uses multiple subtests that all look at different aspects of developing foundational skills. As individual tasks - none of them would be considered “reading” but when combined, they result in fluent word reading. Some subtests, like the Letter Naming Fluency or the Phoneme Segmentation Fluency assessment, are phased out as students progress from Kindergarten to 2nd grade. These tests also provide different weighting based on their relevance and importance to reading at different grade levels. The end result is a composite score which is the best overall measure of reading risk- but it is the sub tests that tell us “why”.

Communicating these tests with parents is also part of our work. We will never simply print out a report of colors and numbers and send it home. In fact the latest Early Screening Guidance from MA DESE - DESE new regulations and guidance on early literacy screenings and notifications , provides clear expectations for communicating with families. We have been communicating the literacy screening results for a couple of years now as part of our dyslexia screening process. This has included a detailed letter, a link to a video explaining the screening and a phone call from a teacher if there are risk factors. But maybe most critical to the communication is not just saying a child is at risk, but rather what we are going to do about it.

The Tiered System Works - especially before that 3rd Grade mark

The research is abundant about how challenging it is to close literacy gaps for kids after third grade. In a recently conducted study, but not yet published, by WestEd for the MA Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, the data about this challenge became even clearer. The study tracked multiple years of screening data from over 25,000 students in MA. The screeners were not just limited to one but rather several approved, valid and reliable early literacy screeners, including the DIBELS 8, which we use. It showed that districts were successful at changing large percentages of kids “risk” levels in Kindergarten and 1st grade. They had the data and were able to provide the targeted instruction. The trend continued with improvements in second grade, but was less dramatic than what was demonstrated in K and Gr. 1. But when the kids reached 3rd Grade, the at risk student percentage was deceased by only a small percentage. Early intervention is key and having the data to know what to do and what to monitor is just the starting point.

In Pentucket, data here from one school, which is reflective of the district, shows the same pattern. We had massive sea changes at Kindergarten and First grade, moving many students out of the “some risk” and “at-risk” categories, into the “green and blue” low risk categories.

We saw some very good movement in grade 2 as well, as we continued to apply a tiered approach. Classroom teachers, reading specialists, special education teachers, literacy tutors and paraprofessionals, all working with students to ensure they get what they are supposed to for whole class instruction, but then using small groups for more targeted instruction for those students who need it.

Then in third grade, we know we are still providing high quality instruction, targeted intervention and highly specialized instruction for a small number of students. This results in some movement with the students who are on grade level, but it also shows that it becomes increasingly difficult to change the outcomes with foundational skills for students by the end of third grade.

Of course these are all different cohorts of students. Ideally, as we apply this model to students year after year, we see less students in need of targeted instruction. In particular, we paid special attention to the students in grade 3 this past year. They were the students, from a foundational literacy skill perspective, who were most impacted by the school disruptions from COVID. The graph below shows them across the district in a cohort model and reflects exactly what we would have hoped but also supports the concept that early intervention on literacy skills is necessary. Big changes are seen in the early grades with less movement from risk categories as they completed third grade.

Some may say we are a little too focused on data. Data is certainly a driving factor in the district’s work on literacy, but it is the student that is at the center. We know what is at stake and that is why we are persistent with the work and use the data to help assess our progress and pinpoint how we can help a student succeed. There is clear progress here, for students and the district, but also more work to do.

The data tells part of the story and is often a great starting point for evaluating progress as a whole and even for individual students. There is, of course, progress in other ways too. With Wit and Wisdom, students in Kindergarten through grade 8 are engaged with more complex text, building knowledge, learning vocabulary, breaking apart sentence structure and examining how syntax and grammar impacts meaning. These are the other aspects of the Reading Rope and just as important. They develop over time and interact with one another, helping students to become more strategic readers and writers but the focus on early literacy foundational skills is what opens the door to those texts.

Brent Conway

Assistant Superintendent

Comments