Literacy Classroom Schedules with a Knowledge Building ELA Curriculum

- Brent Conway

- Sep 25, 2023

- 10 min read

Updated: Sep 27, 2023

Over the past five years the district has been moving their literacy instruction to a tiered system that is based on the science of reading. Now in year three of the implementation of Wit and Wisdom, a knowledge building literacy curriculum, there are many systems that have had to change as well to help successfully implement a High Quality Literacy Curriculum such as Wit and Wisdom.

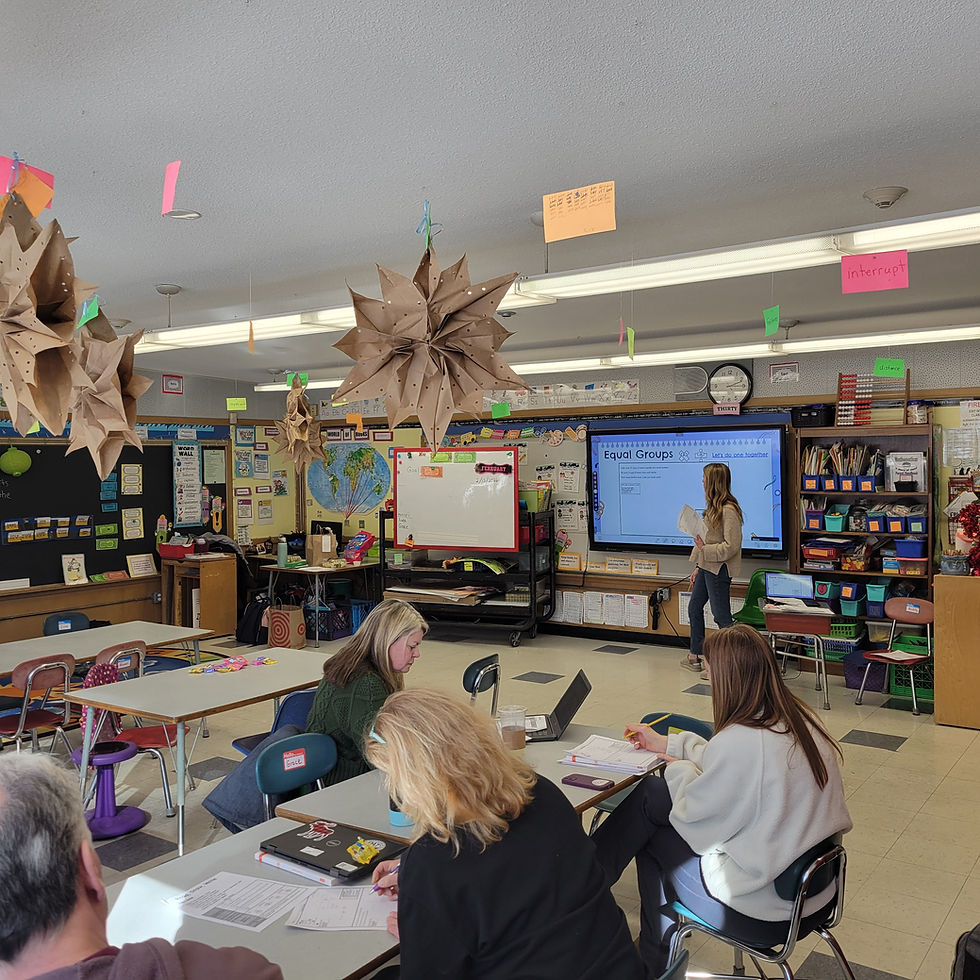

Pentucket was one of the earlier districts in Massachusetts to adopt a knowledge building literacy curriculum and therefore received numerous requests for site visits or insights into how it was different. One of the most common questions asked by teachers and administrators has been “Can we see it? And what does it look like?” The question, while well intended, is not likely to get the answer people are looking for. That is largely because the planning and daily schedule is very different from what schools and teachers had grown accustomed to. Educators, as they think through adopting a new curriculum, are often thinking of implementing it within the same structures and systems they have used. As comfortable as those systems and routines had become, simply put, they don’t really work with something like Wit and Wisdom.

A Reader’s Workshop or Daily Guided Reading Groups with “literacy centers” had become the norm for so many districts in Massachusetts and across the country. Management systems that had students doing activities centered around five literacy tasks each day (sometimes known as the Daily 5) were all part of the classroom management systems teachers were comfortable using. This resulted in a very similar daily structure for each ELA class. Students certainly thrive with structure and routine, and classrooms without structures and routines can quickly devolve into chaotic environments without much focus on learning. So it’s no wonder such systems for literacy management had become so popular. Essentially classrooms had developed a consistent 45, 60 or 90 minute literacy block where students were doing similar activities each day meant to build independence but without much direct instruction on critical literacy needs with language, writing, comprehension and work with grade level text.

These schedules and approaches often addressed all of the critical areas of what had become known as The Big 5 Pillars of reading that had been identified by the National Reading Panel report released in 2000. While this report remains a hallmark for evidence based literacy instruction, the implementation and essentially “covering” areas through a workshop approach has been the core of the mistake. While “The Big 5” remains the basis for reading research - not all five should be taught the same way and the visual of them as equal pillars gives some people a misconception about them.

What we have discovered in Pentucket is that the routine of the schedule has been hard for staff to move away from. They either tried to make Wit and Wisdom “fit” into their long held understanding of a daily class schedule, or fell back into using unneeded and in some cases non-evidence based instruction and supplements as a way to include aspects they thought were still needed. This led to disconnected activities that often were not taking full advantage of a well articulated and high quality literacy program. The intent of such a program is to connect literacy and language skills with instruction that places the text at the center of the planning. Therefore, outside of the foundation skill instruction and practice where we teach students to decode fluently and automatically, a classroom daily literacy schedule would look different each day based on where students were in the core text and what instruction was needed to help students understand the text and respond to it in writing.

In the example linked here from the Meadows Center, which is often viewed as a model schedule that addresses all areas of literacy, the planning is based on an approach that does not place the text at the center. While it may adequately address decoding instruction, and tiered instruction, the focus on comprehension strategies and disconnected writing rather than the complex features of text, is not likely to support the implementation of a high quality, knowledge building literacy program.

We utilize a school wide scheduling model to build a consistent structure to ensure that tiered instruction and targeted instruction is able to be provided in addition to Tier 1 instruction. This building-wide schedule helps to ensure that all students in each grade have a similar experience to literacy instruction and any supplemental or more intensive instruction is available to students who need it. This builds from the core instruction, rather than competing against it or undermining it. These building-wide schedules have been very successful for our tiered approach, but daily classroom schedules are just as impactful to ensure that the curriculum is used in the most effective way it is designed to be used.

What should a literacy block look like?

Our K through grade 3 classrooms still have a set time for foundational skills, ranging from 25-40 minutes in each grade. The daily or weekly routines to teach phonological skills are generally the same with similar activities occurring daily or with some options based on the students’ readiness. However, the intent is to build automaticity with skills, so practice becomes a key part of these routines. Direct, explicit and systematic instruction is a consistent methodology that is not wavered from with regards to foundational skills.

There is no simple answer to the question when it comes to language comprehension though. Certainly the daily schedule, while different based on the text and students, should still seek to make use of routines, expectations and structures for student engagement and interaction. Using Wit and Wisdom, the lessons focusing on language comprehension and writing evolve over the course of the engagement with text and throughout a module on a conceptually related topic. Instructional routines are built into each lesson to establish some consistency, while allowing for flexible use of routines that best facilitate the knowledge and comprehension of the text.

In their paper titled “Placing Text at the Center of the Standards-Aligned ELA Classroom”, Meredith Liben and Susan Pimentel outline the difference from a strategies first focused literacy approach versus the approach that focuses on teaching the complexities of the text to build an understanding of the information conveyed in the text.

“Comprehension strategies are the habits and internalized practices of successful readers. Individuals who enjoy reading expect to understand what they read and do something about it when they do not. They should be activated when the text stops making sense to a reader. Strategies that have scads of evidence supporting their value when confronting difficult text can and should be employed strategically, as the research and their name suggest, and always in service to students’ understanding of the text. But most educators have been taught—and therefore teach—that reading better is a matter of assembling a quiver of reading comprehension strategies to aim at any reading task. Too often, reading strategies are made to be the very objective of a lesson, rather than a means to a larger goal: understanding all that a rich text has to teach and say to us.”

Our literacy block now classrooms, once past the routines of foundational skill work, can vary quite a bit from day to day but also flow based on the point of study the class is with the module or core text. At the start of a text or module more time is spent with the whole class building some background knowledge on the key concept or content and students are engaged in teacher led discussion but student driven observations and discourse. Vocabulary plays an important part during these lessons as students will be expected to know more advanced content specific words that are connected to the text but also words that would be used across multiple domains (known as Tier 2 words) and carry impactful meaning for complex sentences and text.

Knowledge building literacy programs do not follow a routine 5 day cycle, where teachers and students can anticipate a new text or lesson of the week on Monday and a weekly quiz on Fridays. These early lessons in a module will vary based on the type of core text. Non-fiction texts about a science or nature topic may be different from non-fiction about a historical event or time period. Variations in lessons can be seen in different forms of fictional texts as well. The content framing question is the driver. Regardless, the earlier lessons are about focusing the student's interest on the information or question they will be exploring through various texts. The sets of connected lessons have no set cycle of days. Some may run over a 7 day period, while other arcs may be as long as 14 days. The literacy block also makes time for fluency work with the core grade level text for practice without concern for speed. Writing instruction may have less time in a schedule towards the start of the module with a focus on examining the texts as exemplars with a focus on sentence level construction.

A Visual organization of a 75-90 minute Day 1 or 2 literacy block early in a module.

As we advance through the module, the information and sources of information around the centralized question start to mount and students become increasingly engaged in answering the key content question. As the knowledge builds, so do their encounters with complex language. The instruction starts to focus on teaching the aspects of the text that makes it complex and often gets in the way of the reader's comprehension. Grammar, syntax, morphology of vocabulary words and sentence structure from the texts, are part of the lessons that also then connect to writing instruction. While there is no distinct “writing workshop” time, the amount of time spent on writing, all related to the content question and text, increases over the course of the module.

A Visual organization of a 75-90 minute Day 4 or 5 literacy block mid way through an arc in a module.

As the students progress through a core text they are gearing up for an end of module task and writing exercise that has them putting much of the instruction they have received into action, while using the discourse they had with each other and the knowledge building work they did collectively. The time spent on writing into the later days of a focused arc increases. As Natalie Wexler discusses in her Forbes article titled, Putting Comprehension Strategy Instruction Into Perspective, being able to synthesize information from multiple texts is the skill we want our students to do and it requires academic knowledge, vocabulary, and interaction with the complex syntax of the text.

Students are still being taught about key comprehension strategies such as summarizing, but the lessons are shorter and frequently revisited to help students consider when they may use one of the strategies to help create more meaning. They are in fact being to taught to be “strategic” with the strategies. In reality, students may use a variety of strategies and not just one when they read, so our instruction and engagement with complex texts helps students to integrate more than just a strategy of the week through structured practice.

A Visual organization of a 75 minute Day 7 of literacy block towards the end of an arc in a module

“Retired” Practices that were part of our old schedules and routines

With the use of a knowledge building curriculum, such as Wit and Wisdom, there are several practices that had long been part of our former approach that are not reflected now. These practices emerged from balanced literacy and reader’s workshop training and they no longer have a place in our schedule and routines. By placing the text at the center of our work and teacher planning, some of these routines have been essentially “retired.” Specifically, carving out literacy block time for Read to Self or sustained silent reading, is not part of our work now. This should not be construed to mean that we don’t want students to be reading. Of course we do. It is more of a matter of efficiency and working to develop readers who have the capacity to read on their own. For students who have some challenges with reading, either decoding or understanding more complex text, the 20 or so minutes of sustained silent reading just made their struggles go “silent”. This is not a great use of their time and if we just give them easier books to engage with, then we are not helping them to learn to read more challenging text.

Writer’s workshop, at least in its form known to most, is no longer part of our structure. Writing in response to texts that are unrelated to core topics or content is not as effective as writing in response to text and using texts both as exemplars and as sources for evidence and ideas. By using the texts and knowledge building activities, we can capture the benefit of the reciprocal process of reading and writing, for both comprehending the texts students read and for developing more advanced writing structures with sentences.

Another retired practice that is no longer reflected in a class schedule is the use of small group lessons with all students in order to have comprehension lessons. This too, like the two mentioned previously, is a nuanced change as we know that teaching students in small groups can have powerful outcomes. In fact, we still carve out 30 minutes each day for what we call Targeted Teaching Time which is mainly done through small groups. However, if we are working to engage all students with grade level texts, and have them focus their discussions on analyzing the text, this is best done in whole class with frequent breakouts and learning exercises in partners or small groups to increase student discourse. Students who require a more focused level of support and additional scaffolds with teacher guidance can get that support through targeted teaching time. Again this time is in addition to the schedules shown above - but not all students need that. In fact, most should not. The high quality tier 1 instruction, with well designed and connected learning activities, should provide the majority of students with the appropriate learning opportunities with scaffolds as needed.

Impact on Learning

The impact for students is through a more coherent and connected learning experience. All aspects of the curriculum are establishing the context needed for understanding concepts, language and vocabulary. We are not teaching science or social studies during our literacy block. That is not what a knowledge building literacy curriculum is. It is a literacy curriculum, but one that leverages the research we know about background knowledge, vocabulary and text complexity.

Students reading a volume of conceptually related text are able to make connections, both during the literacy lessons and also times outside of the classroom and in future grade levels as well. The focus on content objectives provides purpose and direction for learning.

These changes have not come easy as daily schedules and routines become part of the way teachers organize their rooms, think about their entire day and week. However, with each day, there is more and more progress with the systems change and the outcomes for students are improving with each step.

Brent Conway

Assistant Superintendent

Jen Hogan

K-6 Literacy & Humanities Coordinator and Coach

Comments